Listen on your favorite platform.

Description

In this episode of Math, Universally Speaking, Ron Martiello reflects on a collaboratively designed fourth-grade lesson on equivalent fractions through the lens of Universal Design for Learning (UDL). He shares how intentional planning, precise academic language, and the strategic use of multiple representations helped students develop deep conceptual understanding of fractions.

Listeners will learn how tools like the Frayer Model, anchor charts, visual models, and structured discourse can activate prior knowledge, clarify vocabulary, and support repeated reasoning. Ron explains how moving deliberately from concrete visuals to symbolic equations empowered students to recognize patterns, test ideas, and understand why fractions are equivalent—rather than relying on memorized procedures.

This episode highlights practical teacher moves for supporting diverse learners, including English language learners and students who struggle with academic language, while maintaining high expectations and mathematical rigor. Through real classroom examples, Ron demonstrates how UDL principles can increase access, engagement, and student agency in elementary math instruction.

Whether you are teaching fractions, designing concept-based math lessons, or working to strengthen equity and accessibility in your classroom, this episode offers actionable strategies for building meaningful mathematical understanding.

Show Notes

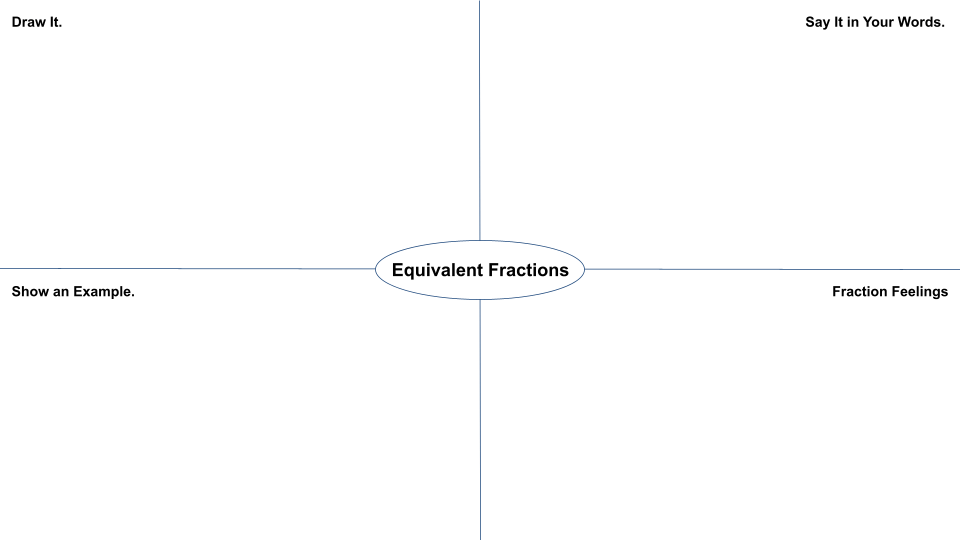

Equivalent Fractions Frayer Model

Make a copy of your Equivalent Fraction Frayer Model

Transcript

This transcript has been professionally edited for clarity and readability. It reflects the content and intent of the conversation but is not a verbatim, word-for-word record.

Teaching Equivalent Fractions: Using and Connecting Mathematical Representations with Universal Design for Learning

Introduction

Welcome back to Math, Universally Speaking—where we explore how intentional design, instructional choices, and teacher moves can make mathematics more accessible and meaningful for every learner. In this episode, we are going to slow down and reflect on how we design math experiences that build understanding, remove barriers to learning, and honor student thinking.

Today, I want to reflect on a fourth-grade lesson on equivalent fractions that I co-designed and co-taught with my colleague Sam Batty. This was one of those lessons that really reinforced for me how powerful, careful planning, shared language, and deliberate instructional moves can be when we proactively plan for conceptual understanding and repeated reasoning.

This lesson was not about jumping in to solve problems. It was about building capacity. It was about laying the conceptual groundwork students need before they engage in more complex fraction work in upcoming lessons. From the start, we were aligned on the purpose: to help students understand what equivalent fractions are, how they are structured, and how we talk about them.

Our focus with this lesson was on teacher moves, especially around clarifying vocabulary and being intentional with language while designing for the variability of the students in the room. We wanted students to attend to and make use of the structure of fractions, not just memorize a rule. That meant being very deliberate about the words we used, how often we used them, and how consistently we paired language with visual and abstract representations.

Before we moved into instruction, it was important for us to understand how students were already thinking about fractions and what equivalent fractions meant to them.

To do that, we began with a Frayer Model as a recall activity providing all students access to the lesson. In the center was the term Equivalent Fractions. Around it were four sections or blocks: one asking for an example, one asking students to explain it in their own words, one asking them to draw a picture, and one asking how they felt about fractions.

We designed those four prompts very intentionally. Each one offered an entry point to the lesson. Students who gravitated toward visuals could draw. Others could write equations or real-world examples. And even if a student wasn’t confident yet in their mathematical understanding, they could still participate by sharing their feelings. Whether they were highly uncertain or extremely confident, everyone had an entry point into the task.

This gave us more than just a snapshot of prior knowledge. It gave us insight into student thinking. It helped us understand not only what students knew, but how they were reasoning and how they felt about fractions going into the lesson.

As we monitored and observed the class, we found that many students carried over some understanding from third grade. They could represent fractions using circle models and bar models and label the models with the correct numerical representation. Many used the equal sign to demonstrate the connection between the model and the fraction. We watched these students carefully because we did not want to give them the misconception that this is what we meant by an equivalent fraction. Others seemed to grasp the concept quickly and showed a numerical representation of two equivalent fractions. When we questioned students about their thinking, their working vocabulary of fractions was not very precise. They may have had some understanding, but could not communicate why their reasoning worked. This was the starting line for the lesson.

After interpreting what we saw, we introduced an anchor chart that displayed the specific vocabulary we planned to use throughout the lesson. This was a deliberate design choice. There is a lot of language associated with the structure of fractions, and we wanted to front-load that vocabulary in a way that was accessible to all learners—especially students who are English language learners or who struggle with academic language.

The anchor chart paired words with visuals so students could connect language to meaning. We kept it visible throughout the lesson so both students and teachers could reference it as we talked, modeled, and reasoned together.

We still weren’t solving problems. Instead, we stayed curious while facilitating discussions. We intentionally and repeatedly spoke about the vocabulary and the structure of fractions. We focused on what fractions represent, what the numerator and denominator mean, and what it means for two fractions to be equivalent.

We used visual models—circle models and bar models—to explore this idea. For example, we looked at five-tenths and one-half. Even though the models had different numbers of equal parts, the amount shaded was the same. The critical idea we emphasized was that if the whole is the same, then the shaded amounts represent equivalent quantities. This was an opportunity to address any possible misconceptions we observed on their Frayer Models at the beginning of the lesson.

Using the visual models, students began to notice patterns on their own. They started to articulate that multiplying the numerator and denominator by the same number created an equivalent fraction. That idea emerged naturally from the visuals—it wasn’t introduced as a rule up front..

As students shared their thinking, we leveraged their language. We positioned them as competent doers of math. We listened intently to what we were hearing and connected it explicitly to equations. We modeled how multiplying the numerator and denominator by the same number results in an equivalent fraction, grounding that symbolic work in the visual reasoning students had already developed.

Throughout the lesson, we were very transparent with students about our instructional choices. We told them directly that they were hearing the same words over and over on purpose. Not because we thought they couldn’t learn it—but because this language matters. We explained that this vocabulary would continue to show up in future lessons, and we expected them to use it as well.

Toward the end of the lesson, we asked some accelerating questions. We asked “Does multiplying the numerator and the denominator by the same number always work when finding equivalent fractions.” I had a lot of agreement around the room. Some students were more compliant than critically thinking until a group of students started creating a counterpoint and said, “No.” When I asked them to tell me more, they said, “You can divide the numerator and the denominator by the same number and it does the same thing. “ That sparked a great conversation about how both multiplying and dividing the numerator and denominator by the same number can work when finding equivalent fractions.

Students then had time to play with different fractions—choosing numbers they were familiar with and testing whether multiplying or dividing the numerator and denominator by the same number still worked. That exploration reinforced their reasoning and deepened their understanding. It was a great way to close our time together and lead students into the next day’s lesson when they would continue working on their understanding of equivalent fractions.

The moves made in this lesson were done so to balance the needs of the learners, while keeping the integrity of the learning goal. By using Universal Design for Learning from the beginning of the design process, we gave all students access to the foundational concept of equivalent fractions and built the capacity for learning more complex topics related to the structure of fractions. We intentionally activated prior knowledge using the Frayer model and honored student thinking by providing multiple entry points. We clarified and reinforced vocabulary and supported understanding through multiple representations, including circle models, bar models, and equations, moving deliberately from visual representations of equivalent fractions to symbolic representations with equations. Throughout the lesson, students experienced choice, autonomy, and opportunities for repeated reasoning. Finally, we provided space for students to extend their understanding, making them a viable resource that impacted the collective understanding of the whole class.

This lesson was a strong reminder that when we design intentionally and teach collaboratively, we can create learning experiences that truly prepare students for the mathematical work ahead.

Closing

As you reflect on your own classroom practice, I’d love to hear from you. Have you used similar strategies or teacher moves to support conceptual understanding in mathematics? How have you been intentional with language, vocabulary, or representations to help students make sense of big ideas?

If you want to learn more about how you can design stronger math lessons, pick up your copy of Conquering Math Myths with Universal Design. It will help you to design more intentional math lessons and meet the needs of all the learners in your class. I also invite you to share your stories, reflections, and classroom experiences and join the conversation with the Math, Universally Speaking community on LinkedIn, Instagram, or Facebook using the Hashtag #mathuniversallyspeaking. We grow stronger in our practice when we learn from one another.

Take care.

Professional Development Questions

- How do our instructional choices around vocabulary and language either support or limit students’ ability to reason about fractions conceptually?

- In what ways are we being intentional about repeating, modeling, and reinforcing academic language so students can use it independently over time?

- How are we using multiple representations to move students from visual reasoning to symbolic understanding?

- How do we ensure that models, diagrams, and equations are meaningfully connected rather than treated as separate steps or shortcuts?

- How does our lesson design reflect Universal Design for Learning by providing multiple entry points and opportunities for student agency?

- How are we activating prior knowledge, honoring student thinking, and creating space for exploration and repeated reasoning before introducing formal procedures?

References

CAST. (2024). CAST Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 3.0. https://udlguidelines.cast.org

National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. (2024). Principles to actions: Ensuring mathematical success for all (10th anniversary ed.). National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Rufo, J. M., & Martiello, R. (2024). Conquering math myths with universal design: An inclusive instructional approach for grades K–8. ASCD.

Leave a comment