Description:

Productive Math Struggle with Kevin Dykema

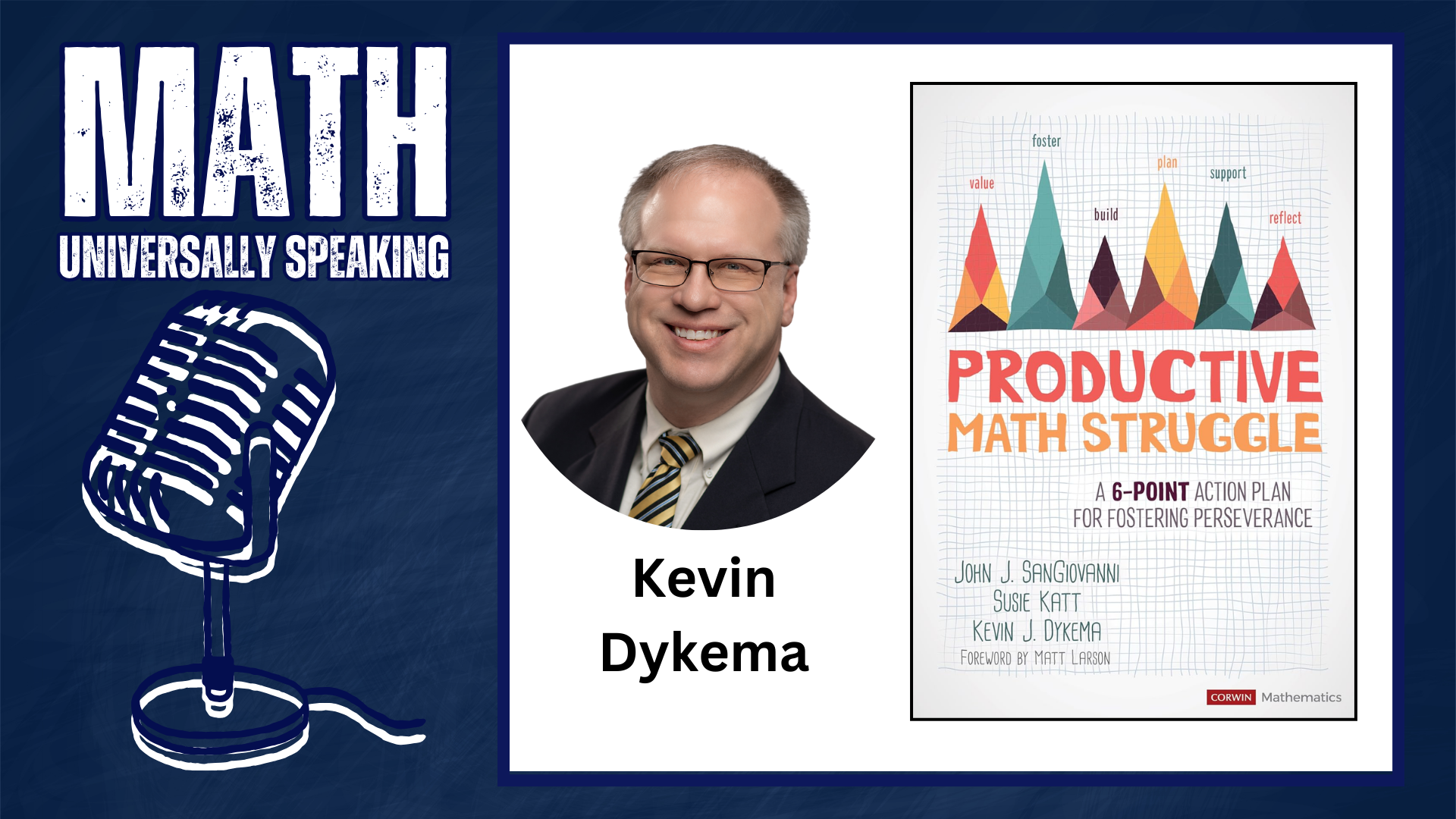

🎙️ Episode 10: Productive Math Struggle with Kevin Dykema

Join nationally recognized math educator and former NCTM President Kevin Dykema as he unpacks what productive math struggle really means—and what it doesn’t. In this powerful conversation, Kevin shares reflections from his 26 years in the classroom, his leadership at NCTM, and his co-authored book Productive Math Struggle. Hear how he advocates for equitable math instruction that moves students beyond memorization toward deep understanding. If you’re looking for practical, honest insights about how to support all learners through meaningful struggle, this episode is for you.

Don’t forget to follow the podcast and join the conversation using #MathUniversallySpeaking.

Transcript

Episode 10: Productive Math Struggle with Kevin Dykema

Episode 10: Productive Math Struggle with Kevin Dykema

Ron:

Hello, Math. Universally speaking, this is Ron Martiello, and I have a very special guest for you today. Today’s guest is a nationally recognized math educator with over 26 years of classroom experience. He’s a dynamic speaker, and I could say that because I’ve heard him speak. And he is also a very strong advocate for equitable math instruction. He served as president of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics from 2022 to 2024 and is still very active with the NCTM. He is co-author of Productive Math Struggle. Please welcome to the podcast. Kevin Dykman, Hi Kevin.

Kevin:

Hi Ron. It’s a pleasure to be here. Thanks for having me, and thanks for thinking with me about how do we better make math instruction to help more and more students have a successful time?

Ron:

You’re very welcome. And someone who has had a career like yours, I loved the bio that I’ve read on you and the number of things that you’re doing. I mean, you’ve been to Washington recently to advocate for good math instruction. You’re an author. You’ve been the president. You stood up in front of 1000s of people. Like tell us a little bit more about your journey.

Kevin:

Yeah, and I will say that standing in front of 1000s of people at an NCTM conference, the great news is the lights are so bright that you can’t see anybody that’s out there. So there could be three people, there could be 3000 and it wouldn’t make me any more nervous, because you just can’t see it. But taught eighth grade in southwest Michigan for many years. At 26 years in the classroom, I became involved with my local state affiliate, and then somebody said, Hey, Kevin, would you consider being on the NCTM board? They said, Sure. And I ran, and much to my surprise, was elected. And I served on that board from 2016 to 2019 and then a couple years later, it became time for nominations for President. I started getting all these weird text emails from a variety of different people saying, Hey, we think you ought to consider running for it. So I spent some time thinking about it, and much to my surprise, I said, Sure. And even much greater to my surprise, I was elected, and it was such an honor and a joy to represent mathematics educators in that role. And you know, as President of NCTM, every moment is completely and totally different. You know, you mentioned beyond Capitol Hill, I was on Capitol Hill numerous times, meeting with a variety of people trying to advocate for high quality math instruction professional development for teachers, getting media requests. I met with, you know, some place that nobody’s ever heard of, but then there’s places like the Wall Street Journal called one day and wanted a quote for something. And it was just amazing to them to think I, the president, is a spokesperson for, then the council, and just meets with a variety of different things. And it was such a wonderful role just to deeply think about, how do we help all of our students learn math? And I think historically in math, we’ve done a great job of helping some of our students be successful. Those that are going into STEM careers get great math education. Those are going to be engineers, those that are going to become math teachers, but not all of our students have that same experience. So I’m always looking for what can we do differently? What can I do differently in my classroom to help meet the needs of students? Since my presidency ended, I still do some work with NCTM. I’m also doing some instructional coaching in my district and working with teachers and helping them figure out what can they do differently. And that role is such a powerful role and such a fun role, I get the opportunity to go into teacher A’s room and then teacher B’s room and say, Oh, have you thought about doing this? And most of the time it’s just something I saw in teacher A’s room, but it makes me look really, really smart, and some days I need the help looking looking smart, so it’s been a wonderful career, and I look forward to continuing to serve mathematics educators to help us all continue to grow. And I don’t think that our learning is ever done, because students are constantly changing. The world around us is constantly changing, and so we need to constantly change, and we need to be willing to try a variety of different things to better meet the needs of students.

Ron:

And you know, that’s why my colleagues and I, you know, we definitely read all your emails when you put them out there as president, and we’re also following you on the podcast through NCTM and with you and Latrenda. And so, you know that is something that we connect to, is that equitable message making sure that all students can do math at high levels, and making sure that we’re providing that access we’re very big on, like, you know, that should not be that gatekeeper subject. It should be an accelerator. And we just, you know, your message gives us courage as we continue our work as instructional coaches and sharing it with our teachers.

Kevin:

And it’s hard work. I mean, it’s hard work to meet the needs of all of our students. It would be much easier in many respects to say, Ah, I mean, teach it this way. If you don’t get it, you need to fix yourself and adapt to me. But it’s much tougher for me to say, All right, hey, I’ve tried these three things that I’ve done in the past, and it still hasn’t worked for you. I don’t mind just do the slower and louder approach. I need to do something different and to better meet your needs. And it’s challenging work, but yet it’s work. Then that keeps me, and I know many people, it keeps us rejuvenated, and it’s so fun to think about, what can I do differently, and then to see that aha moment on that kid’s face, when that that student who’s been working hard at grappling with those ideas finally makes sense, and you just see their their whole face light up. Those are the moments that keep me in education. Those are the moments that I absolutely live for.

Ron:

That’s awesome. So and you so you support your teachers face to face. You support your teachers through the podcast, through the NCTM. You also support teachers through this, this book that you co wrote with Susie Katt and John SanGiovanni called productive math struggle. Now I saw you speak at an event, and my boss won the book, and I asked to him if I could borrow this for this interview. He’s not getting this back. This is a great book.

Kevin:

Well, thanks. We enjoyed writing the book, and it’s one of those topics that people talk about, but there was no there was no professional resource available to educators prior to us sitting down and doing it, and when we sat down and wrote it, we tried to be as class and applicable as possible. And I know that, you know, we have some of the theory in there, but it’s for every one of those six different actions. It’s really, what does this look like in your class? And we try to be very, very practical. And we’ve learned a lot, and the book was released in 2020 right at the very start of the pandemic. And in the last five years, as I’ve worked with a variety of different districts, doing presentations, doing some consulting work with different spots, I’ve learned even more about professional learning and more about productive struggle. And it’s one of those areas that we can continue to grow and continue to really focus on, how can we better meet the needs of our students through having them make sense, rather than us just standing in front saying, Here’s Step one, here’s step two, here’s step three. And boring some of our students to death.

Ron:

I love speaking with people like you. You and I are very like minded, because, you know, we I have podcasts. You do podcasts. You know, we were both authors, and it’s like, you know, we don’t do this. It’s not celebrity, it’s about the message, and we’re still learning. That’s the first thing I say to people, like, I’m still learning. So tell me what you have.

Kevin:

Absolutely and there are times you know that I’ll join a book study and you know, I’ll say, here are things that I’ve learned since the book was published. And minutes, yeah, it’s, it’s amazing, and it’s great. And every time I talk with somebody about that, and, you know, every time I work with a district, every time I present at a conference, I always learn more things. And people ask a question like, oh, I never thought of it that way, or I hadn’t considered that. And it’s, it’s great, and that’s we talk about our students being lifelong learners. But I think as adults, we need to be lifelong learners as well. And you know, as you noted, authors are still continuing to learn about their own work.

Ron:

Yeah, I’m still trying to figure out what I want to be when I grow up. So but let’s, let me ask you this question here. You had talked about sometimes productive struggle can be misunderstood in your words, what is productive struggle and what isn’t productive struggle?

Kevin:

Yeah. So what it isn’t is completely and totally hands off for the teacher that sometimes people, when they hear this notion of productive struggle, they, you know, they automatically jump to inquiry based learning, which is a very good connection. There anything the teachers just completely and totally hands off. The kids are going to come up with whatever they’re going to come up with, and we just are happy with whatever the kids well, that’s baloney. Anybody who says the teachers are completely, totally hands off, and the kids just make up their own understandings. They need to get into a K 12 classroom and spend a significant amount of time in there. And I think, you know, when I look at productive struggle, it’s really the teacher is providing opportunities, providing those structures for the students to grapple, for the students to make the connections, for the students to make understanding. So I think that’s what it is. I mean, it’s, it’s one of those things that it’s tough to come up with a real nice, concise, two sentence definition of what it is, but it’s, it’s really about getting the students actively engaged, getting the students grappling. I love that word, and that’s a word that the NCTM used in principles to action when they describe productive struggle, it’s getting the students, grappling, getting the students and making the connections. Really it’s moving math from math by memorizing, which is what many of us experience as students, to this math by understanding. I want my students to understand what’s going on, not just have a series of steps memorized.

Ron:

And that’s the classroom that I, you know, we all wish we grew up in. I mean, I went to Catholic school in Northeast Philadelphia for years. There’s one way. And I would have loved to have just, you know, talked about things, but talking was cheating too. So there was a lot, there were a lot of barriers to the math as well intentioned as our teachers were. So I want to pull a quote from the book, and this kind of segues right into what we were just talking or from what we were just talking about. Productive struggle cannot be valued if math is not valued beyond the right answers. Tell me more about that quote, what it means to you.

Kevin:

Yeah, and I love that. I love that quote. And I think some people, when they read it, they say, oh, math education doesn’t care about correct answers. I do. My students get correct answers. Let me be clear about that. I’m not advocating. John and Susie wouldn’t advocate for who cares about the answers. It’s all about the process. We do care about the right answers, but we also care about the process. And I wonder, how many times does a student do a series of problems get them all wrong? They assume they know absolutely nothing, when in reality, we know oftentimes, they’re very close to getting that. And I want that. I really wanted to be part of student thinking. How is the student thinking about that problem? How can I how can I help that student really? How can I rescue that student’s thinking? How can I really help build upon them that partial conception and get to that to that final answer at that point in time. So I do care about right answers, but it has to be more than just caring about the right answer. It has to be able to process the students are using. How many times do we have students who you know in class when you’ve just told them what to do, they can they can regurgitate it correctly, and then the next day, when you give them a little problem, like, we’ve never done this before, like, Yes, you did. This is what we did yesterday. The madness needs to stop. And when we when we focus so much just on getting them the right answer, that’s the madness we need to be focusing on, on helping our students understand. What is that process? What’s that journey that’s leading to that good conceptual understanding and that good procedural fluency.

Ron:

So you use the word rescue. Tell me how we can rescue thinking with some struggle moves. You talk about struggle moves in the book.

Kevin:

Yeah. So I think there’s a difference between rescuing their answers and rescuing thinking. And I think in math education, many of us grew up having our answers rescued, and many of us may have started out our career. I started out my career rescuing students’ answers. I was so focused on that, but I really want to rescue their thinking. So I think there’s a couple of things that we can do. One of the things that I try to do my own classroom, my planning looks different now, as I do my lesson planning, I mean, I’m picking out what problems I’m going to do and what tasks I’m going to do, but I’m also thinking about, how would I go about doing that problem, how would I go about doing that task? But more importantly, how might my students do that both, what are some correct ways they may go about doing that, and let’s be honest, not all of our students do the math problems the same way that I would do it. Not all of them think the same way, and that’s a joy. So like to think about what are some correct ways, but also to think about what are some false starts they may make. What are some incorrect things? And when I do that planning ahead of time, think about what are those correct paths? What are some of those incorrect paths? That allows me to plan some reactions. It allows me to come up with some good questions of what I might do. For example, you know, I have two sort of go-to questions that I love to ask a group, and I’m working with them when I want to really rescue their thinking. Lot of times, you know, sit down at their group and say, All right, hey, I am sure. I am confident that you’ve already spent a lot of time considering what to do for this problem. Name one thing that you’ve already tried, and as soon as I acknowledge Hey, you’ve already done some thinking about it, tell me one thing you’ve thought about it that’s starting to open up that door for them to share their thinking. Another one. Another question I love to ask and say, if there was just one thing that if you knew the answer to it, would make the whole problem that much nicer. What would that one thing be? Now teaching eighth graders oftentimes will say, we wish we knew the answer to the problem. And I always try to say, I wish I knew the answer to the problem right now too. But what’s another thing? And so often I think our students say, I can’t do this problem, and it’s really, you know, they know 95% of the problem. It’s one little part that’s dubbing their toes. So it’s really getting to that. So I had to be conscious of making sure that the questions I’m asking are really leading to that thinking, asking and trying to elicit. What have you already thought about this problem? Where is that? Thinking? I have found it’s better to be not helpful enough than to be too helpful. If I’m not helpful enough, they can ask some follow up questions if I’m too helpful. I’ve never had a kid that says, stop, go away. I’m good now at this point in time, right sort of undo the too much helping, but you can definitely add on to that. So I try to err on the side of caution and not give them enough help.

Ron:

Otherwise they’re just waiting for you. Yeah, you’re kind of training them to…Well, you just wait for me. I’ll help you in a minute. And it’s like, then the thinking is gone.

Kevin:

Without a doubt.

Ron:

So you so we talk about how that could be something that is learned if we enable kids too much by over helping them. What is but how do you foster an identity for productive struggle? How do we get kids to kind of like, grasp this and own it?

Kevin:

Yeah, and that’s the challenging part, and that’s a tough part, but it’s such an important part. And part of this fostering identity is we need to be concerned about fostering that identity. If we don’t care about how our students view themselves as a mathematician, there’s no reason to even consider doing that. And you know, sometimes I think, you know, with an exit ticket, we’re focused so much on the answer. And again, I care about correct answers, but I also care about how do they see themselves in terms of that? And, you know, sometimes I think, you know, I could have student A and Student B, they both get two out of two correct on the exit ticket. I make the assumption they’re both ready to move on. They’re both doing well, when, in reality, Student A is two out of two, and they feel very confident. But Student B got those same two questions right, but they’re feeling very, very unconfident, and they think that those I guess, is all wrong. If I’m not doing something to identify that, I’m doing myself a disservice, but more importantly, I’m doing my students a disservice. So I really like to think about, you know, I need to do something to identify those student identities. I need to be asking those questions. Part of it is making sure that I’m clear about what I mean by student identity. And when I think about a mathematical identity, I really view it as, you know, their perceived, their own perception of their ability to participate in math. And for being honest, we have a math crisis in the United States, a math identity crisis. It is completely and totally socially acceptable, perhaps even socially cool, to say I’m not good at math. You don’t hear people saying I’m not good at reading, they may say, I don’t enjoy reading. I much rather have a person says I don’t enjoy math, I’m not good at math, then at least I see there’s, there’s some progress to that. Another part of the identity, you know, is identifying identity, knowing what identity is. But I also think it’s helping students see themselves as a mathematician. You know, oftentimes, when you ask them to describe a mathematician, at least my students say it’s an old person, oftentimes a dead person, a white male, oftentimes with frizzy hair. We need to be exposing our students to other mathematicians. We need to help our students recognize that people are still learning math. They’re still figuring out math. That math was developed and is being developed to solve real world solutions. It’s not our real world problems. It’s not like someone just came up with these things just to make our lives miserable or to make the students lives miserable. But so often students see that. So I love you know, like when 60 minutes has a feature about a teenager who discovered something new. There’s my mathematician of the week for that next week. So I’m constantly looking on the lookout for a variety of mathematicians that aren’t Pythagoras, Gauss, Euclid, not the ones that they’re normally exposed to, expose them to a variety of things because the house and recognize, oh, it’s not just the Greeks from however many 1000s of years ago that can do math. I can do math still. Women can do math. People who aren’t white can do math, and it’s a very helpful thing.

Ron:

So I was in my 40s when and diving into my current coaching career here when I started realizing, like, wait a minute, math isn’t isolated. Another myth. It’s somebody in a room sitting in a chalkboard for hours into the night trying to solve a math problem. When there are communities of mathematicians who are solving like math that is like beyond some of the things that we ever touch in school. So how do you bring that back to the classroom? How do you bring that understanding and what does a community of productive struggle look like?

Kevin:

Yeah, so I think about building that community. I need to make sure I’m putting some structures in place so that the community is supportive of not just being told here’s what to do, and not just making a math by memorizing. So it’s really laying those foundations for here’s what struggles gonna look like. Productive struggles look like. Here’s what’s not gonna I’m gonna look like. Here’s what managing our frustration is gonna look like. Here’s what not managing our frustration might look like. So students that work at the beginning of the year, just laying some of those norms, not the rules, but the norms of what is it going to look like? And then it’s continually reinforcing those norms throughout the year, thinking about, you know, how do we persevere? Maybe I have an anchor chart. Maybe I have a “what do I do when I’m stuck chart” that just stays in the front of the classroom, the side of the classroom, something where they can have that, that reminder. I know that if I’m not paying attention to building a supportive community, a community is going to get built, but it’s not going to be one that’s supportive. It’s going to be one that’s a destructive thing. So it’s really just being conscious at the beginning of the year, reinforcing it throughout the year. What does it look like in there? And a lot of reminders. I mean, I taught eighth grade for those 26 years. They’re adolescents. They’re at that awkward stage in their own minds. They need to be reminded, Hey, it’s okay that you can get it right now. Because remember, three months ago, you didn’t get it and you didn’t give up, and lo and behold, now you do have it. So they need those reminders. I need those reminders.

Ron:

So as we’re reminding them, one of the I’ll tell you, one of the things that I is near and dear to my heart is reflection. And with the limited time that math teachers sometimes have due to instructional minutes transitions in the day. You know, tell me a little bit more about the role that reflection plays in productive struggle as teachers try to build time for it.

Kevin:

Yeah. So I really see sort of three different roles for reflection. The first role, I mean, the students, just need to have that reminder that your perseverance, you’re continually grappling, you’re not giving up, led to you finally understanding it at that point in time. So they need that reflection, just that reminder of it. A second thing, when we spend time doing reflecting that allows us to celebrate that and what kid doesn’t like, to celebrate what kid doesn’t like, sort of that pat on back. I mean, what adult doesn’t like that pat on the back? And you know how many of us as educators have that Manila file folder full of of student notes? I mean, now they’re probably emails that I print off and do that, but you know, when I first started teaching, they actually would write little notes once in a while. Notes. Once in a while, you get that note from a parent or something, and you know, if you’re “feel good file”. We like it as adults, our students like that. That feel good thing. So I need to do some sort of celebration with it. But I think a third aspect of reflection, you know, the students need that reminder of the that it led somewhere, and the students need to have that celebration. But I think that third aspect of reflection is from the teacher end. As a teacher, I need to spend some time at the end of the day reflecting back on how things went. I need to jot myself some notes of, hey, here was a great question that I just thought of on the spur of the moment. Here was a question that I thought was gonna be great and was a flop of a question. Don’t ever use that question again. And I think sometimes I know, as an earlier career teacher, I get to the end of the day and be like, I need to focus on tomorrow. Well, I’ve learned I need to spend three or four minutes focusing on today, summarizing today, thinking about it, and jotting yourself some notes that when I teach that same concept again. 364, days from now, I’ve got some good ideas for it. So, reflection such a powerful thing. I don’t need to spend hours doing the reflection in my classroom. I can do that in one two minutes. Do that as part of the wrap up. Do that quick celebration. Do those quick reminders. I can spend three to five minutes after school, jotting myself a couple of quick notes. So I don’t think it needs to be a laborious, time intensive thing. But isn’t that we need to do if we’re truly meeting the needs of our students.

Ron:

That’s awesome. And I love how you turn attention to teachers, because they need all kinds of support to make sure that this goes because this doesn’t happen without them. We so appreciate them. Do you have any other advice for them as they work toward productive struggle in math class?

Kevin:

First I want to acknowledge making change is difficult no matter what, making the shift to getting our students engaged in more productive struggle is difficult, and because it’s difficult, it’s not gonna go perfectly all the time. And we need to be patient with ourselves. We need to forgive ourselves. We need to say, Oh, I tried that once. It didn’t work out so hot. That doesn’t mean never do it again. That means I need to reflect back on how could I do it differently? Because it’s different for me, but it’s also different for the students. And I think sometimes we get in our own way that we expect things to be perfect right off the bat. I mean, we tell our kids when they’re learning, oh, it’s going to be bumpy, bumpy for us when we’re learning a new thing as well. My biggest piece of advice is I work with teachers on really implementing productive struggle and getting our students doing more of the grappling. It’s just be patient with yourself. Forgive yourself. It’s gonna take time, but keep your eye on the prize. Keep your eye on the students. Our goal, my goal needs to be, what am I doing to help every single kid learn and the way that we have traditionally taught math, the way that many of us may have learned math or is just memorized, the steps the teacher told you what to do did not work for all of my classmates. I know it does not work for all of my students. So if I’m truly interested in meeting the needs of my students, I have to be willing to try to do things differently to better meet their needs. And I know that getting our students grappling, making sense of the mathematics, helping them persevere, develop those skills, is such a vital thing, and it’s going to benefit them in math and in life in general.

Ron:

Awesome, Kevin, we’re coming to the end of the interview, and I just want to ask you one more question. Do you have any final thoughts you want to kind of leave our listeners with? You know, you’ve put it all out there. You’ve answered my questions. But you know, what else is there anything else you’d like to add?

Kevin:

Love your job. Love your job. Being a math educator is a wonderful career. You get the opportunity to take what’s often a dreaded subject for students and make it much more palatable for them. Make it where they recognize they are capable of learning math, and keep it focused on the kids. I mean, there’s all kinds of other junk that happens in a school day, and you deal with a whole bunch of other stuff, but remember, you’re in it for the kids. You’re in it to help a student have a good experience with with math in that 45 minutes, that 60 minutes, whatever you have in your math block, in your math class.

Ron:

Awesome. Well, Kevin, I want to thank you so much for taking the time today. You are a busy guy, and we appreciate the time that you gave us to go over productive struggle. And to give us your perspective on it, people, you need to go take a look at this book, Productive Math Struggle: A Six Point Action Plan for Fostering Perseverance. It’s awesome that you could read it front to back. You could read it a chapter at a time. There are tons of strategies here. Again, my boss is not getting this back for a little while, so I’m gonna dive in this summer, Kevin, thank you again and thank you for all you do.

Kevin:

Thank you

Listen To Kevin Dykema and Latrenda D. Knighten on Adding It all Up (The Official NCTM Podcast)

💬 Professional Development Questions

- Reflection & Discussion (Individual or Group)

- Kevin Dykema emphasizes the importance of student thinking and struggle in the learning process.

- How do you currently support productive struggle in your classroom?

- What challenges do you face when allowing students to struggle, and how might you reframe those challenges?

- Kevin discusses making learning visible and accessible through modeling and representations.

- In what ways do you currently use multiple representations in your math instruction?

- How could you intentionally use visual or concrete models to make abstract concepts more accessible?

- Kevin shared a story about teachers building student confidence by focusing on what students can do.

- Reflect on a recent moment when you celebrated a student’s progress rather than perfection. How did that impact the student’s engagement or mindset?

- He encourages us to listen to student thinking rather than rushing to correct it.

- How might you create more space in your lessons to allow students to explain their thinking?

- What norms or routines can be established to value student reasoning in your classroom?

- Kevin Dykema emphasizes the importance of student thinking and struggle in the learning process.

- Action-Oriented Questions

- Looking at your upcoming math unit, identify one lesson where you can emphasize productive struggle.

- What scaffolds or supports might you remove to encourage deeper thinking?

- How will you communicate to students that struggle is part of learning?

- Consider Kevin’s message about not robbing students of the opportunity to learn.

- Are there moments in your classroom when you tend to jump in too quickly with help or answers?

- How might you replace that impulse with a question, prompt, or wait time?

- Looking at your upcoming math unit, identify one lesson where you can emphasize productive struggle.

References:

SanGiovanni, J. J., Katt, S., & Dykema, K. J. (2020). Productive math struggle: A 6-point action plan for fostering perseverance. Corwin Press.OpenAI. (2024). ChatGPT (Mar 14 version) [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com/

Leave a comment